Apple’s most senior engineers and its marketing chief sat down with The Independent to discuss the company’s new M1 laptop chip that’s replacing Intel silicon in Macs.

Apple’s marketing boss Greg Joswiak, software engineering chief Craig Federighi and hardware engineering head John Ternus spoke with The Independent shortly after Tuesday’s “One More Thing” Apple Silicon Macs event has finished.

Federighi explains they couldn’t believe how quite a step up in terms of speed the M1 really is:

We overshot. You have these projects where sometimes you have a goal and you’re like, ‘well, we got close, that was fine.’ This one, part of what has us all just bouncing off the walls here – just smiling – is that as we brought the pieces together, we’re like, ‘this is working better than we even thought it would.’ We started getting back our battery life numbers and we’re like, ‘You’re kidding. I thought we had people that knew how to estimate these things’.

Ternus added:

This was just building momentum within the teams who were so passionate and excited about this product that they just wanted to keep pushing, keep optimising: ‘How much better can we make it? How much better we can make it?’”

Apple has been through these major transitions before: For instance, back in 2005 the company announced that it would change from PowerPC processors to Intel chips.

Federighi commented:

We’ve done this before. We’ve watched others in the industry do it in the meantime, not so successfully. But we’ve, I believe, really perfected these sorts of transitions, we know exactly how to handle the tools to make it really easy for developers.

Joswiak on how they came up with the chip’s name:

I think M1 makes a lot of sense for a Mac chip. ’A’ was started for the phone chips at Apple and since then we’ve tried to use letters that make sense: the chips for our headphones use ’H,’ you start to feel the trend there. We’re brilliant marketers that way.

On how the M1-powered Air and Pro can stay distinct if they have the exact same chip:

’Thermal capacity,’ says Federighi decisively. The Pro has a fan – Apple calls it an ’active cooling system’ – while the Air doesn’t and the rest of the performance flows from there.

Indeed, The Verge joked that the biggest difference between the new MacBook Air and MacBook Pro is a fan, which the Air doesn’t have (but is still thicker than the Pro). Federighi also poured cold water on speculation that Apple might be working on a touchscreen Mac, based on the macOS Big Sur aesthetic borrowing slavishly from the iPhone and iPad.

I gotta tell you when we released Big Sur and these articles started coming out saying, ‘Oh my God, look, Apple is preparing for touch,’ I was thinking like, ‘Whoa, why?’ We had designed and evolved the look for macOS in a way that felt most comfortable and natural to us, not remotely considering something about touch.

You haven’t even remotely considered bringing touch to the Mac?

We’re living with iPads, we’re living with phones, our own sense of the aesthetic – the sort of openness and airiness of the interface – the fact that these devices have large retina displays now. All of these things led us to the design for the Mac that felt to us most comfortable, actually in no way related to touch.

Let’s revisit his statement in a few years to see how well it has aged.

I’ve never felt more comfortable moving across our family of devices as a user, which I do hundreds of times a day moving between iOS 14, iPadOS 14 and macOS Big Sur. They all just feel of a family – there’s just less cognitive load to the switching process.

He’s right on the seamless transitions between Apple screens.

It’s just they all feel like the natural instantiation of the experience for that device. And that’s what you’re seeing, not some signaling of a future change in input methods.

Glad we sorted that out.

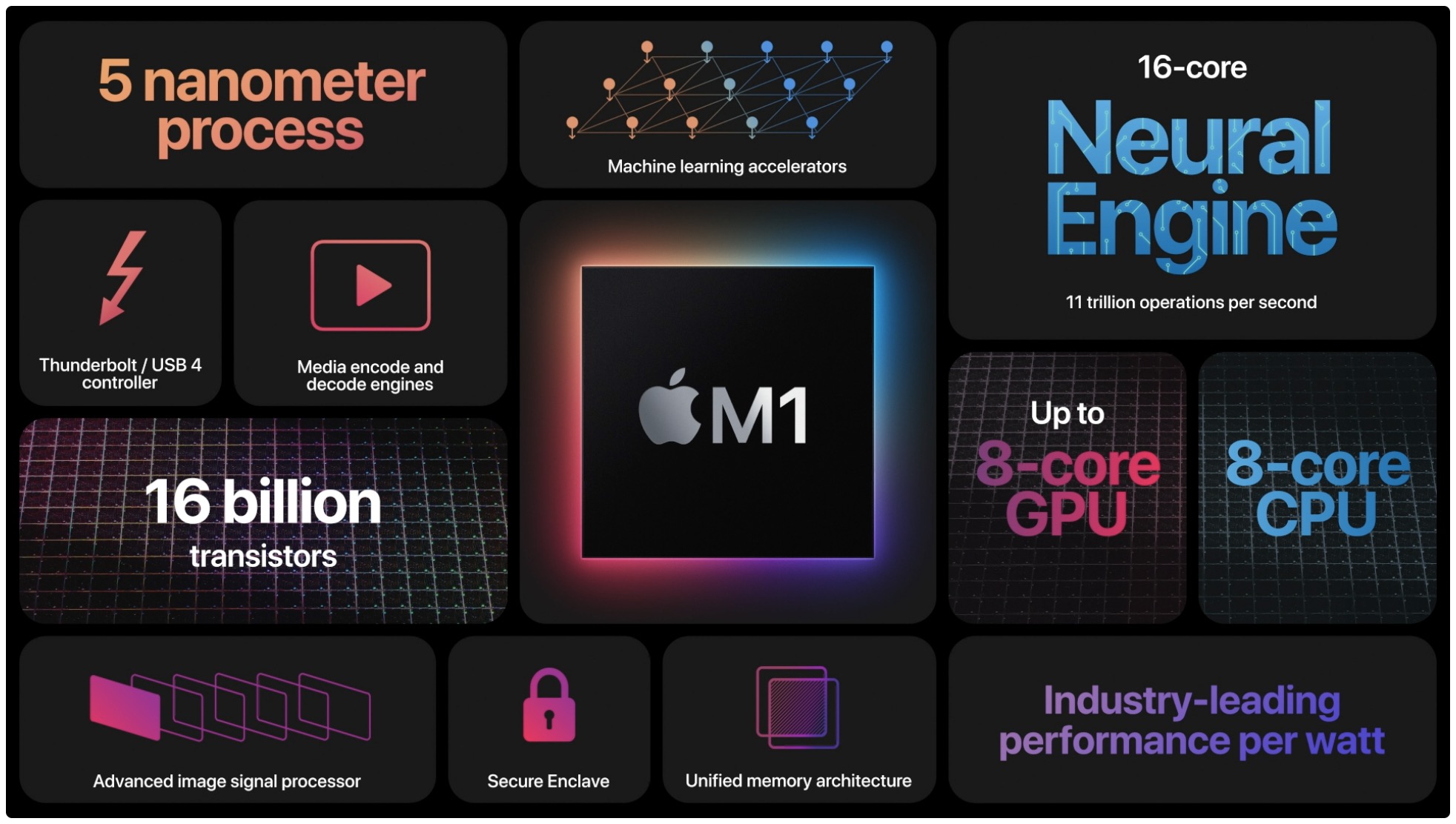

The inaugural version of the M1 powers the MacBook Air, 13-inch MacBook Pro and Mac mini, which are all systems that previously used notebook chips and notebook-class graphics.

For its more powerful Mac computers, like the high-end MacBook Pro notebooks, the all-in-one iMac desktop and the Mac Pro, Apple will need to come up with even faster chips. According to Bloomberg, Apple has envisioned a family of custom chips for Macs. According to the company, the whole lineup should transition to Apple Silicon in about two years.

Until then, I’ll be imagining the kind of crazy performance that might be possible with a future Apple desktop chip in a massive tower computer with vast fans, such as the Mac Pro.