A certain hit-and-miss Asian trade publication (I know, don’t start) reported this morning that the initial shipment of a sixth-generation iPhone could be disrupted due to yield problems with in-cell panels the device is believed to adopt.

Apparently, suppliers are experiencing yield rates too low to generate profits, despite the fact that Apple allegedly offered an estimated $10-15 per-panel subsidy. Really, what’s up with in-cell tech and the next iPhone?

First, here’s from DigiTimes:

The poor yield rate of in-cell panels is likely to cause certain disruption to Apple’s shipping schedule for the new iPhone, according to the rumors.

Japan Display’s current yield rate is pegged at just fifty percent, which is insufficient to make profits and ramp up production. Sharp’s yield rates reportedly have not been improved much, prompting Apple to request that Sharp “undergo the validation process again”.

Also, this:

Due to the poor yield rates, combined shipments of in-cell panels for the upcoming iPhone are estimated at only 4-5 million units in July – far below Apple’s target of 20-25 million for all of the third quarter, the rumors pointed out.

However, Apple is still encouraging the panel suppliers to make more at any cost, and is even providing support including subsidies to help lower their production costs.

Even if the report is true, Apple could always turn to TPK’s full-lamination process for the new iPhone.

Why insist on in-cell technology?

Simple: the panels are thinner and Apple needs thinner displays to bring the next iPhone under 8mm (the iPhone 4S is 9.3mm thick) in order to compete with ultra-thin smartphones from Samsung and other makers.

So, I have a couple issues with DigiTimes’ report (and yes, these are biggies).

Firstly, Apple has pretty much announced the next iPhone event through its unofficial mouthpieces, namely Bloomberg, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal (not counting The Verge, The Loop, AllThingsD and other blogs with a strong track record).

This begs an important question: why would Apple go to trouble of (unofficially) announcing its fall iPhone event, and have big media put its credibility on the line unless the company is 100 percent positive that its suppliers are able to ramp up production?

And secondly, the next iPhone is said to have either entered production or is about to. Ironically, DigiTimes also reported recently that production of the next iPhone is now underway.

That Apple is going to use in-cell display technology is a forgone conclusion at this point. A May report by Taipei Times first indicated that iPhone 5 will feature in-cell display panels provided by Sony. Then the credible Wall Street Journal piggy-backed on that story with a mid-July report claiming that Apple “will use a new technology that makes the smartphone’s screen thinner”.

The Journal asserted that Apple will procure these displays from as much as three sources: Sharp, LG Display and Japan Display, a mega-company created by combining respective mobile display operations of Sony, Hitachi, Toshiba and the Innovation Network Corporation of Japan.

Another confirmation came when Wintek, Apple’s existing panel supplier, announced a notable drop in June earnings, another indication that it may have lost out on key orders from Apple.

Here’s a little backgrounder on in-cell displays.

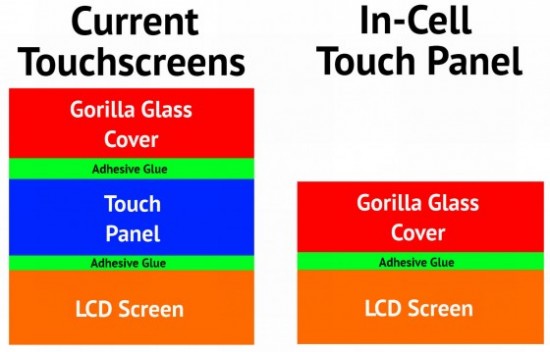

In-cell touchscreen technology eliminates a layer by building the capacitors inside the LCD assembly itself. This reduces the visible distance between the user’s finger and on-screen content within millimeters, resulting in a more direct interaction. In-cell technology also allows for more responsive touchscreen performance.

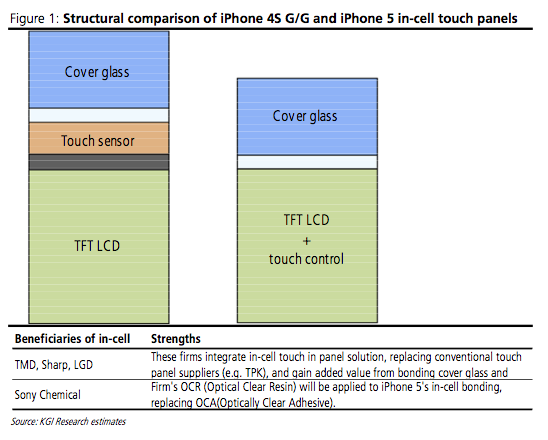

Analyst Ming-Chi Kuo of KGI Securities recently estimated that in-cell touch panels will shave 0.4mm off the next iPhone by removing the separate touch sensor layer and one layer of adhesive.

Image via AppleInsider

According to Kuo, one of the advantage of using in-cell touch is “the shorter lead time for touch panel, its most valuable component, and adjusted activities at the supply end, allowing more precisely tailored products to meet market needs, eventually reducing production costs by an estimated 10-20 percent”.

The in-cell manufacturing process, the analyst observed, would require an estimated three semi-finished items at bonding versus the six required to produce the iPhone 4S. Also cool, the number of production days required could drop from 12-16 to 3-5.

So, DigiTimes.

Fail, no?