Current CEO Tim Cook under Steve Jobs used to run Apple’s vast network of suppliers and contract manufacturers and has largely been credited with turning the company into a well-oiled money-printing machine. But making sure trains run on time involves the incredible complexities associated with hiring tens of thousands of workers – and fast, too – who tediously assemble iPhones and iPads in factories located in China and Taiwan.

Apple and its manufacturing partners have been taking a lot of heat over worker treatment in these sweatshops so the iPhone maker eventually started tracking the work hours of 1+ million supply chain workers and took other proactive measures to ensure fair hiring.

But now, another issue is making headlines: the inhumane treatment of would-be employees by employment brokers who take high advance fees from workers and their families, contrary to Apple’s rules. Read on…

A lengthy piece by Bloomberg Businessweek’s Cam Simpson titled ‘An iPhone Tester Caught in Apple’s Supply Chain’ shares the story told through the eyes of 27-year-old Bibek Dhong who’d found himself $1,000 in debt to recruitment agents before he even started work at Flextronics, a Singapore-based company which commands a whopping 28 million square-feet of factory space spread across four continents.

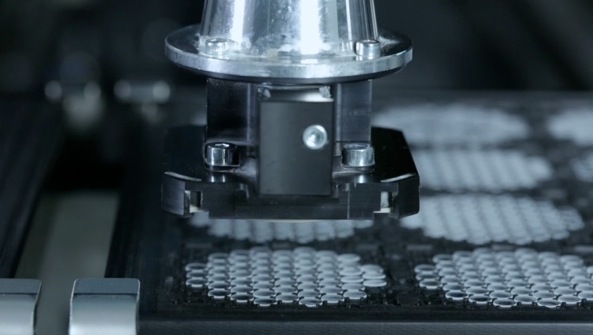

After Apple contracted Flextronics to make cameras for the iPhone 5, the manufacturer turned to brokers to help find 1,500 individuals for the job.

Apple instructed Flextronics to cover brokers’ fees so they don’t take fees from the workers.

But brokers didn’t adhere to Apple’s rules.

In an effort to maximize profits, brokers commissioned subagencies which took fees from the workers. More often than not, brokers would take a year’s worth of salary.

Dhong grabbed a black-and-tan backpack holding his shaving kit, a single change of clothes, two Bibles (one in Nepalese, one in English), and three family photos. He said goodbye to his crying wife and daughter, then jumped onto a microbus on a loud and dusty Kathmandu road.

As promised, the third agent was at the airport, holding Dhong’s passport. He demanded money, but Dhong had nothing left to give. So the broker told Dhong to sign a debenture agreement promising to pay $400 more. If Dhong didn’t sign and if he didn’t quickly pay, he would lose the job. He had yet to start work, and already he was $1,000 in debt.

Some subagents even brought in workers from neighboring countries, like Nepal and Malaysia, often taking their passport as a precaution. As workers pay fees to several brokers and sub-brokers, often times they’re force to take shark loans just to cover these inordinate expenses.

Having wired home much of their money in anticipation of following close behind, many started running out of cash. Then they ran low on food. The first to go hungry were among a group of younger men who had relied on a local restaurant outside the hostel to give them a meal a day on credit.

The owner cut them off when he found out they’d lost their jobs, Dhong says. Hunger soon spread to almost everyone.

Dhong lost his job after Flextronics shuttered production over quality control issues.

Without his passports or cash, Dhong found himself jobless, hungry and in debt.

Because he needed to pay high interest rates on loans, Dhong had no choice but borrow more money to pay for another job abroad, digging himself a deeper hole as a result.

The biggest issue here is that brokers bend Apple’s rules:

Alok Taparia, the managing director of Transworld Manpower, another of the four Nepalese brokers retained for that drive, says he was given clear instructions: Workers shouldn’t be charged; Flextronics would pay the brokers.

But Taparia and the other Nepalese brokers say Flextronics demanded so many men so quickly that there was no way to do it without tapping the country’s network of subagents, stretching into Himalayan villages reachable only by foot.

Sub-contractors are not directly hired by Apple or Apple’s suppliers and are instead commissioned by suppliers’ employment brokers.

Apple is clearly aware of the problem, Bloomberg writes, “As Apple itself has described in reports on its supply chain, the subagents always charge”.

Apple in 2009 attempted to bar suppliers from using workers who’d been charged more than one month’s net factory wages, the story goes, but it only made issues worse.

Last year the company’s audits turned up $6.4 million in fees paid by workers beyond the company’s prescribed limit—compared with $6.7 million in the previous four years combined. And Apple audited fewer plants last year than it did in 2011. The company orders its suppliers to refund workers charged beyond its limit.

These are the harsh realities of working in Asian supply chain.

But then again, would any American take these jobs?