The world’s most powerful government has locked horns with the world’s most powerful corporation in a battle that Apple implies has the potential to affect civil rights for a generation. As you know, the Justice Department gave Apple until February 26 to respond to its court order.

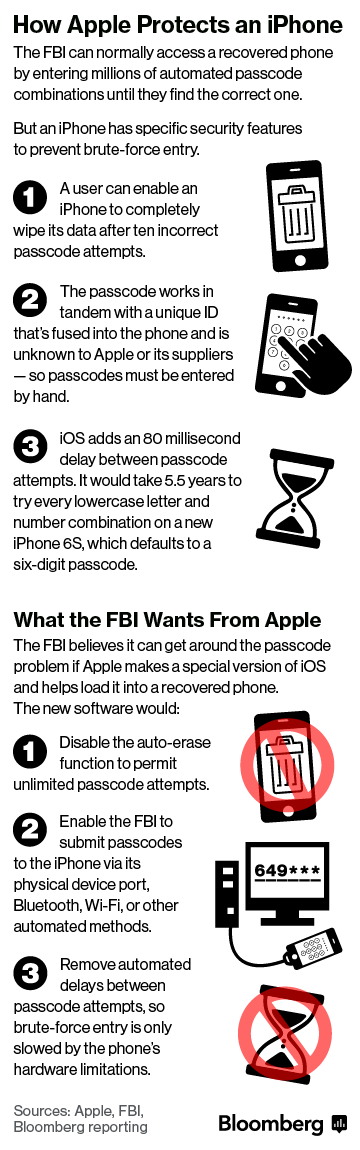

In it, the government is asking Apple’s engineers to create a special version of iOS that would allow brute-force passcode attacks on the shooter’s phone electronically.

Now, some people have suggested that the government’s experts could make an exact copy of the phone’s flash memory to brute-force its way into encrypted data on a powerful computer without needing to guess the passcode on the phone or demand that Apple create a version of iOS that’d remove passcode entry restrictions.

While this is technically feasible, the so-called de-capping method would be painstakingly slow and extremely risky, here’s why.

NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden said the technique described further below could be used to hack the shooter’s phone unilaterally.

“The FBI has other means,” he said during a virtual talk hosted by Johns Hopkins University on Wednesday. “They told the courts they didn’t, but they do. The FBI does not want to do this.”

The FBI doesn’t want to employ the de-capping technique because it carries a great risk of completely destroying the phones’s chip and losing access to its memory forever.

How Apple protects iPhones

When you create a new passcode to protect your device, iOS’s mixing algorithm tangles it with a 256-bit device-unique secret key, called UID, to create the so-called passcode key, which is used as an anchor to secure data on the phone (Apple does not store iPhones’ passcode keys on its servers nor can it access them on the device).

Infographic via Bloomberg.

As a result, brute-force passcode attempts must be performed on the device in question. The problem is, iOS has a user-selectable option to erase all data on the phone after a total of ten failed passcode attempts. In addition, the phone’s hardware imposes delays after an incorrect passcode entry to make the guessing process even harder.

After four incorrect passcode entries, you must wait one minute. This time delay increases to five minutes, 15 minutes and finally one hour. This makes brute-force passcode attacks performed on the phone using a so-called IP box an impractical process.

In addition to requiring a physical possession of the device, IP boxes take about half an hour to break a 4-digit passcode on a pre-iOS 8 device, up to months to break a 6-digit passcode and years, possibly decades, to break complex alphanumeric passcode, both of which are supported on devices running iOS 8 or later.

That being said, making an exact copy of the phone’s flash memory that could be brute-forced off-site, using the power of a supercomputer, would require the Feds to get hold of the phone’s actual UID and the mixing algorithm, both of which are incredibly well secured.

Prying the chip open

Doing so would require the agency to remove and de-capsulate the phone’s chip and expose it to invasive microscopic scrutiny in order to exploit the portion of the chip containing exactly that data.

And herein lies the rub.

Using a focused ion beam, the FBI could drill into the chip micron by micron and then use infinitesimally small probes at the precise target spot to extract both the UID and the data for the mixing algorithm.

They could then use the UID in conjunction and the mixing algorithm on some of the phone’s encrypted flash storage data and try all possible passcode combinations on a supercomputer, until one makes the data readable. As brute-forcing would be done outside iOS, there would be no 10-try limit or self-destruct mechanism that would otherwise wipe the phone’s flash storage clean.

Unfortunately, the process isn’t at all as trivial as it sounds.

“If they screw up, if that laser or that X-ray is a couple of nanometers in the wrong direction, the whole chip is fried and they’ll never get any data off the phone,” said, Dan Guido, co-founder of the cyber security firm Trail of Bits.

“This isn’t a cakewalk,” he said.

The whole process could be a months-long endeavor and “carries a real risk of destroying the chip completely,” as per Senior Security Consultant at IOActive and a hardware reverse engineering specialist Andrew Zonenberg.

According to Apple’s iOS Security Guide, each iPhone’s UID along with the mixing process (called “salt” in cryptography talk) is protected within the Secure Enclave, a special cryptographic co-processor embedded into the A7 chips and above.

Each Secure Enclave is provisioned during fabrication with its own unique ID, states the document. “The device’s unique ID (UID) and a device group ID (GID) are AES 256-bit keys fused (UID) or compiled (GID) into the application processor and Secure Enclave during manufacturing,” reads the document.

On pre-A7 devices, like the shooter’s iPhone 5c, the UID is fused into the main application processor. In addition, the UID itself is connected to the AES cryptographic circuitry by a dedicated path on both devices with the Secure Enclave processor and pre-A7 devices.

Making matter even more complicated, the UID “is not accessible to other parts of the system and is not known to Apple,” nor is it known to its suppliers, according to iOS Security guide. All iOS sees is the output of encrypting something with the UID, not the UID itself.

Wrapping it up

Both Apple’s company-wide memo to employees and its Q&A reiterate the company’s intention to fight the case, as made public in an open letter issued to customers on its website last week, signed by Tim Cook. The Cupertino firm is opposing the FBI’s request to create an iPhone backdoor because that one-off version of iOS could fall in the wrong hands—and with these things it’s a matter of “when”, not “if”—and then undermine the security of every iPhone user out there.

In addition, foreign governments would then be able to leverage this as an excuse to seek similar concessions from Apple for themselves.

FBI Director James Comey insists this is “about the victims and justice” and not “about trying to set a precedent or send any kind of message.”

Read our recap of last week’s events in the FBI vs. Apple case.

Source: KTIC Radio