A highly interesting technical article published October 1 on Apple’s Machine Learning Journal blog has gone unnoticed, until today.

In it, Apple lays out in detail how the untethered “Hey Siri” feature takes advantage of the hardware, software and the power of iCloud to let customers use their assistant hands-free.

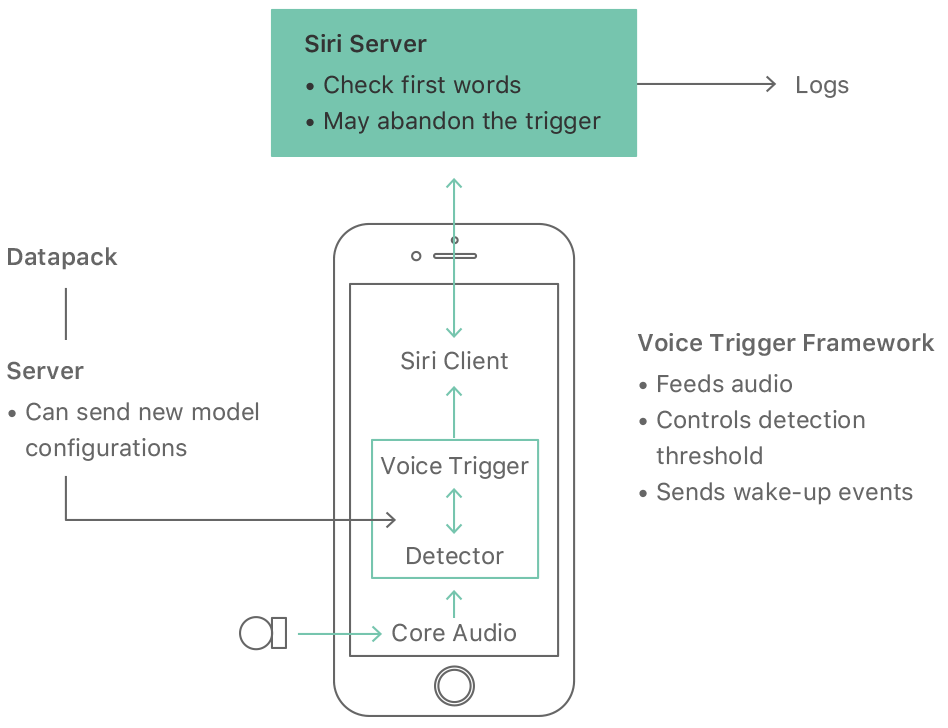

The system couples cloud-based speech recognition, natural language interpretation and other services with hardware-assisted on-device processing. An iOS device runs “a very small speech recognizer” all the time, which listens for just the “Hey Siri” phrase.

The microphone in your iPhone or Apple Watch records 16,000 streams of instantaneous waveform samples per second. Here’s why that doesn’t tax your iPhone battery much or monopolize other system resources, like the RAM and CPU:

To avoid running the main processor all day just to listen for the trigger phrase, the iPhone’s always-on coprocessor (AOP, which is a low-power auxiliary processor embedded into Apple’s M-series motion coprocessor) has access to the microphone signal on your iPhone 6s and later.

We use a small proportion of the AOP’s limited processing power to run a detector with a small version of the neural network. When the score exceeds a threshold the motion coprocessor wakes up the main processor, which analyzes the signal using a larger neural network.

Due to its much smaller battery, Apple Watch runs the “Hey Siri” detector only when its motion coprocessor detects a wrist raise gesture, which turns the screen on—that’s why you cannot use “Hey Siri” on Apple Watch when the screen is off.

WatchOS allocates “Hey Siri” approximately five percent of the limited compute budget.

So, how do they recognize the actual “Hey Siri” hot phrase in real time?

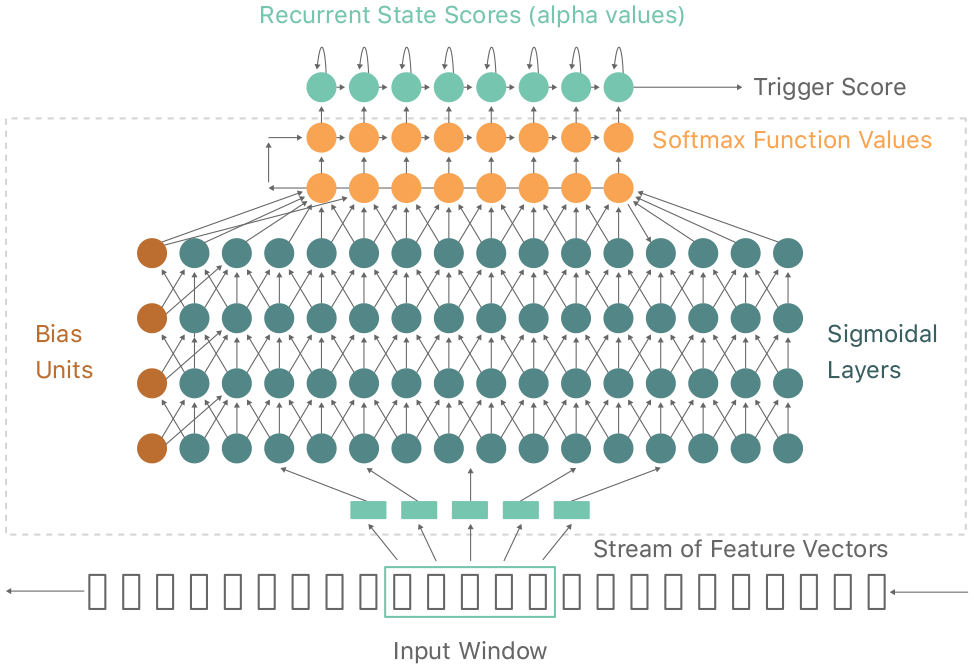

Once captured by your device, the waveform is broken down into a sequence of frames, each describing the sound spectrum of approximately 0.01 sec. About twenty of these frames at a time (0.2 sec of audio) are passed to the deep neural network.

There, the sound is converted into a probability distribution over a set of speech sound classes: those used in the “Hey Siri” phrase, plus silence and other speech, for a total of about 20 sound classes. It then computes a confidence score that the phrase you uttered was “Hey Siri”.

If the score is high enough, Siri wakes up.

On iPhone, they use one neural network for initial detection (running on the power-sipping motion chip) and another as a secondary checker (running on the main processor). To reduce false triggers, Apple also compares any new “Hey Siri” utterances with the five phrases saved to the device during the ”Hey Siri” enrollment process.

“This process not only reduces the probability that ‘Hey Siri’ spoken by another person will trigger your iPhone, but also reduces the rate at which other, similar-sounding phrases trigger Siri,” explain the research paper.

The device also uploads the waveform to the Siri server.

Should the main speech recognizer running in the cloud hear it as something other than “Hey Siri” (for example “Hey Seriously”, “Hey Syria” or some such), the server sends a cancellation signal to the phone to put it back to sleep.

“On some systems, we run a cut-down version of the main speech recognizer on the device to provide an extra check earlier,” Apple notes. I assume that by “some systems” they mean devices connected to power, like Macs, Apple TVs and perhaps even iPads.

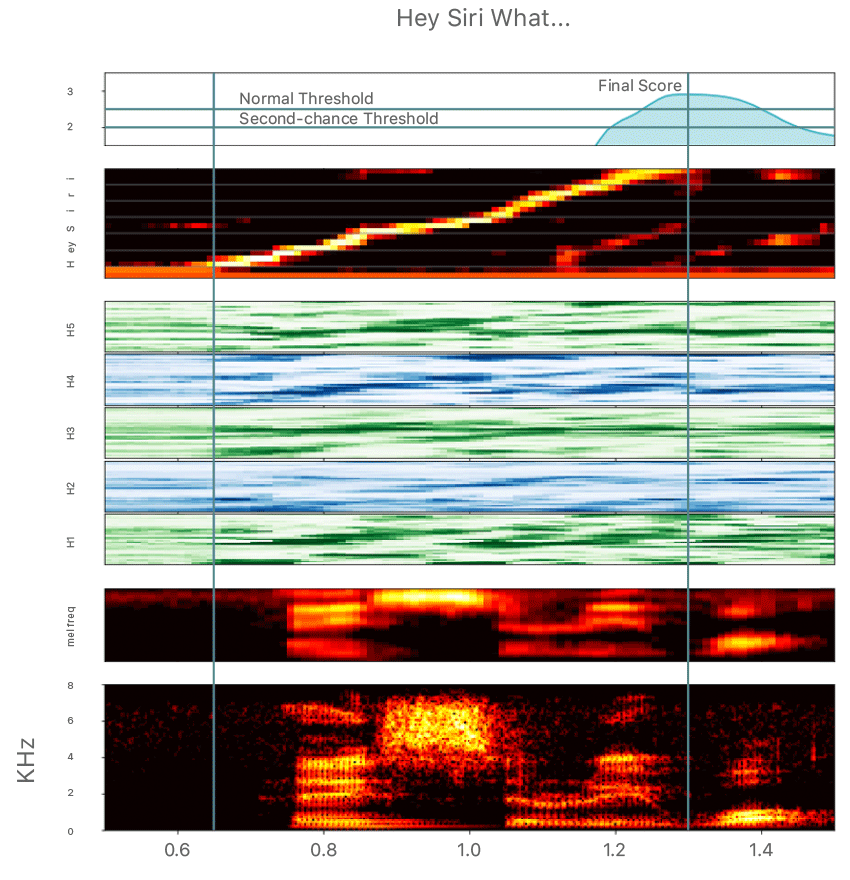

Pictured above: the acoustic pattern as it moves through the “Hey Siri” detector, with a spectrogram of the waveform from the microphone shown at the very bottom. The final score, shown at the top, is compared with a threshold to decide whether to activate Siri.

The threshold itself is dynamic value because Apple wants to let users activate Siri in difficult conditions—if it misses a genuine “Hey Siri” event, the system enters a more sensitive state for a few seconds. Repeating the phrase during that time will trigger Siri.

And here’s how they trained the acoustic model of the “Hey Siri” detector:

Well before there was a Hey Siri feature, a small proportion of users would say ‘Hey Siri’ at the start of a request, having started by pressing the button. We used such ‘Hey Siri’ utterances for the initial training set for the US English detector model.

We also included general speech examples, as used for training the main speech recognizer. In both cases, we used automatic transcription on the training phrases. Siri team members checked a subset of the transcriptions for accuracy.

The acoustic model in US English even takes into account different first vowels in “Siri,” one as in “serious” and the other as in “Syria.”

Training one model takes about a day and there are usually a few models in training at any one time. They generally train three versions: a small model for the first pass on the motion chip, a larger-size model for the second pass and a medium-size model for Apple Watch.

And the last tidbit: the system is trained to recognize localized “Hey Siri” phrases, too.

For instance, French-speaking users say “Dis Siri.” In Korea, they say “Siri 야,” which sounds like “Siri Ya”. Russian-speaking users use the “привет Siri “ phrase (sounds like “Privet Siri”) and in Thai “หวัดดี Siri” (sounds like “Wadi Siri”).

“We made recordings specially in various conditions, such as in the kitchen (both close and far), car, bedroom and restaurant, by native speakers of each language,” says Apple.

They even use podcasts and Siri inputs in many languages to represent both background sounds (especially speech) and the “kinds of phrases that a user might say to another person.”

“Next time you say ‘Hey Siri’ you may think of all that goes on to make responding to that phrase happen, but we hope that it ‘just works’,” Apple sums it up nicely.

The highly technical article provides a fascinating insight into the “Hey Siri” technology we take for granted so be sure to give it a read or save it for later if you’re interested in learning more.